Learning Center

Generate narratives in response to reading

november 13, 2023

For most states, the writing portions of standardized assessments are all rooted in reading. Information gleaned from sources is used to generate an argumentative or informative response. But for some tests, there is also the possibility of a prompt that requires a narrative response. To be clear, these prompts require students to demonstrate comprehension by supplying textual evidence from one or more of the provided texts. Students are NOT simply writing personal narratives.

Such narrative responses typically fall under one of five types.

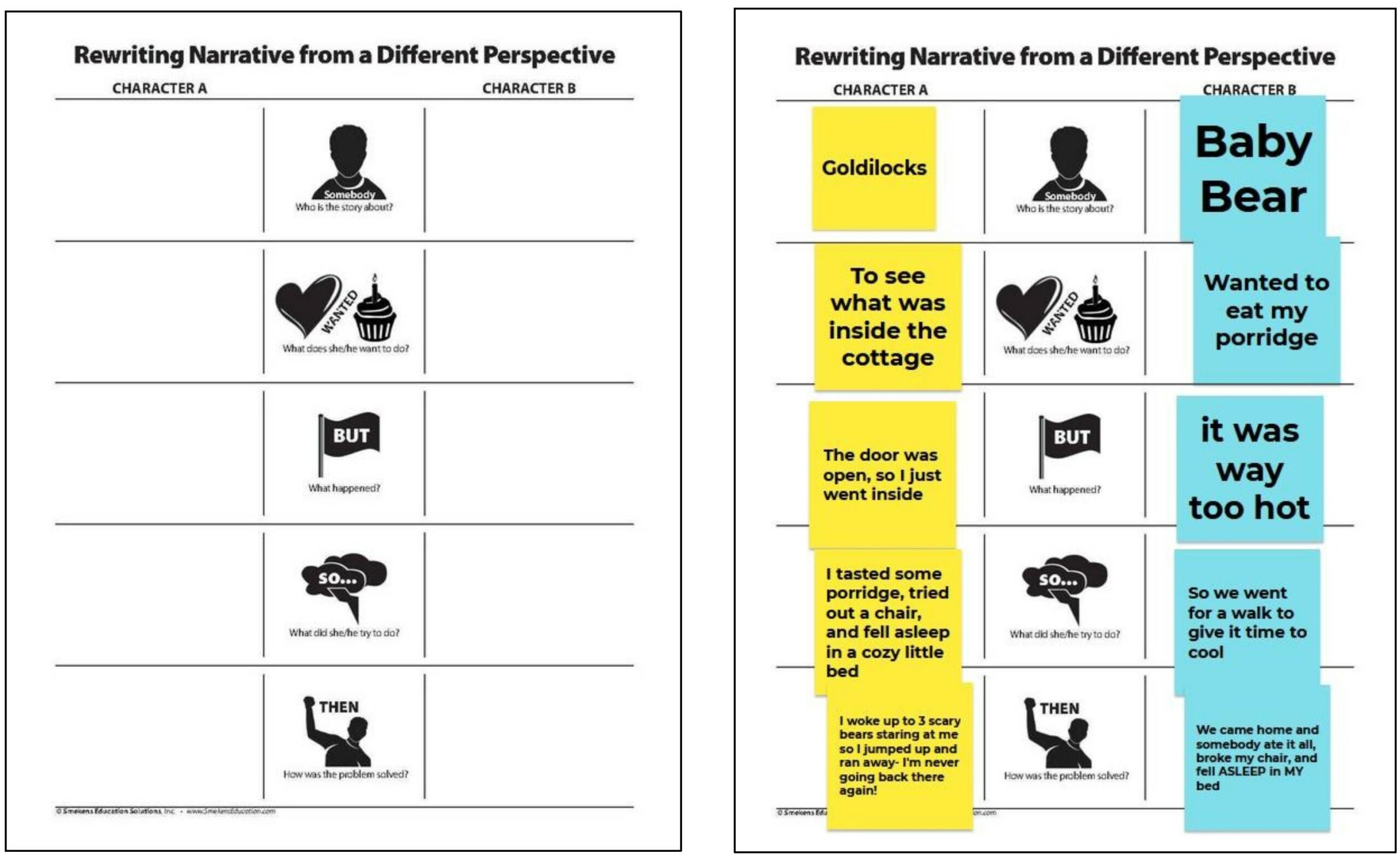

1. Rewrite from a different character’s viewpoint.

After reading a fictional text, students may be asked to rewrite the same story, with the same problem, ending in the same way, but from a different character’s viewpoint. Compare this to fractured fairytales. This written response requires students to know which plot details to repeat and what facets to elaborate on.

To execute this response, students need to first identify the known story elements of the original text. Then, they have to consider them through the lens of the second character.

Rewrite narratives from a different character’s perspective.

Rewrite narrative perspective.

Template | Baby Bear Example

2. Continue the story.

After reading a story, students may be asked to predict what the characters might do the next time a similar situation occurs. This is often compared to book sequels where the same characters face another problem.

After reading a story, students may be asked to predict what the characters might do the next time a similar situation occurs. This is often compared to book sequels where the same characters face another problem.

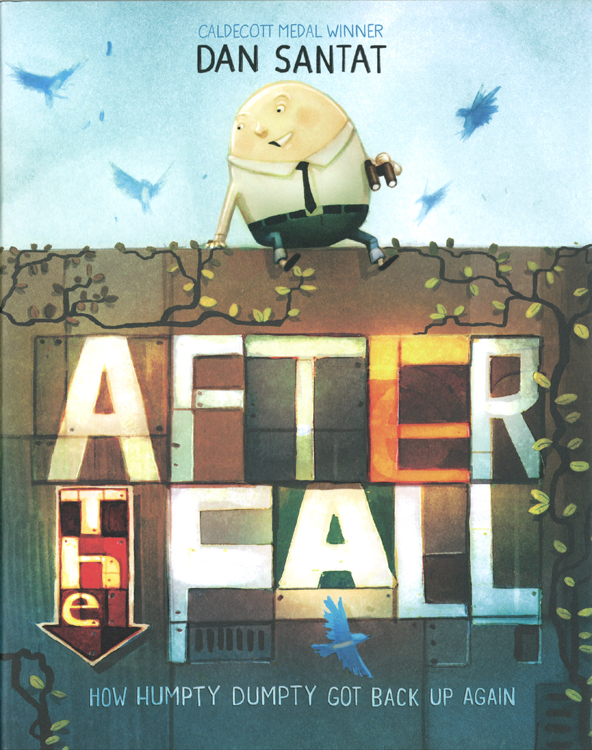

For example, in the original nursery rhyme, Humpty Dumpty has a great fall off a wall. Quickly review the original story, then reveal Dan Santat’s picture book After the Fall. This is a great example of this continue-the-story narrative task because it picks up right where the original ended. It starts with Humpty Dumpty walking out of the hospital after his previous accident.

The plot of the second story (the one students write) should demonstrate a conflict similar to that which was described in the original story. And the solution should include a similar theme or life lesson learned. This proves that students comprehended the original text, understood the prompt, and knew how to write in the narrative structure.

3. Insert the missing part/page.

The third narrative-response option asks students to insert a missing excerpt. Think of these like the deleted scenes from movies. Such “gaps” occur when time moves quickly between actions, when events are merely mentioned, or conversations between characters are only referenced. Students insert the missing part into the middle of the plot.

The third narrative-response option asks students to insert a missing excerpt. Think of these like the deleted scenes from movies. Such “gaps” occur when time moves quickly between actions, when events are merely mentioned, or conversations between characters are only referenced. Students insert the missing part into the middle of the plot.

This type of narrative writing task is especially difficult because it requires students to recognize that they are not writing an entire story. They are only using details known from the beginning of the text in their excerpts without altering or changing the outcome. These inserted portions must stay within the parameters of the original text, honoring plot, setting, character traits, etc.

The first three narrative writing tasks are all based on literature. The final two narrative-response types ask students to write their own realistic fiction; they are writing fiction based on fact.

4. Write an historical fiction.

Students first gather information from several nonfiction texts on a social studies concept. Then they create a plausible character problem that fits the context of the setting described within the informational text.

5. Write a sci-fi.

The same approach used with social studies texts above can be applied to science, too. After reading informational text about a science concept or principle, students generate a science fiction. Again, their narratives have to include a character who faces a problem that gets solved. Within the problem and/or solution, the writer must incorporate facts learned from the nonfiction passage.

These tasks are difficult and require lots of practice. Look for opportunities to weave these read-write responses into your narrative units, rather than only writing stories based on personal experience.

After students have had opportunities to experience these types of writing tasks, remind them that they are writing a response to reading and, therefore, must provide text evidence. Consequently, teach students how to incorporate evidence from the original text(s) into their narratives.