Learning Center

reading

Reveal 3 categories of character lessons

january 26, 2021

Even though determining a text’s theme is an expectation from grades 1-12, many educators wrestle with how to teach this ELA standard—and plenty more students wrestle with how to figure it out.

To help students master inferring a text’s theme, teachers must make this abstract concept concrete and explicit. Here are three facets to an introductory lesson series.

Step 1: Define theme

Like any new concept, teachers would likely start with a definition. Most explain the theme to be a lesson that the author attempts to teach his readers. More than just enjoying the story, an author wants his readers to mature, grow, and learn from the characters’ experiences. By including a bigger life lesson—a theme—an author can have a lasting impact on the reader that continues far after the plot ends.

Step 2: Explain that theme is inferred

Acknowledging that often students are “looking” for the theme, explain that authors don’t tell readers the lesson—they teach it.

Except for the occasional moral that is literally stated at the end of a fable, readers will have to infer the bigger message. So students are not to look for theme, but the details that imply it.

This requires analyzing the actions, choices, and changes a character exhibits. The same realization a character experiences is typically one that the author believes everyone should learn.

Step 3: Give examples

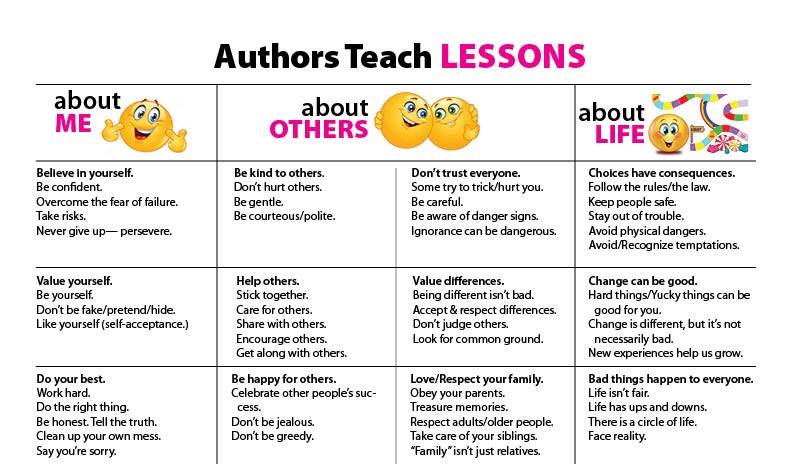

Armed with a stronger understanding of what the theme is and where it is “found,” the next essential step is to build students’ background knowledge. This includes telling them the three most common categories a lesson would fall under:

Lessons about others.

The author is trying to teach me a lesson about how I engage in relationships with others.

Reveal a couple examples of actual lessons per category. Consider previously-read texts, popular songs, traditional fairy tales, and well-known movies that students are familiar with. Review the plots and name the lessons that each of those main characters learned.

Depending on the texts and characters you reference:

Note that a list of lesson examples is most helpful when each is paired with a familiar character who actually learned the lesson through the solving of a problem. The chart alone is only mildly useful.

Consequently, consider building a classroom bulletin board or virtual bulletin board that includes lesson categories with example texts. (Adding book covers or mini-movie posters would be a quick visual reminder as well.)

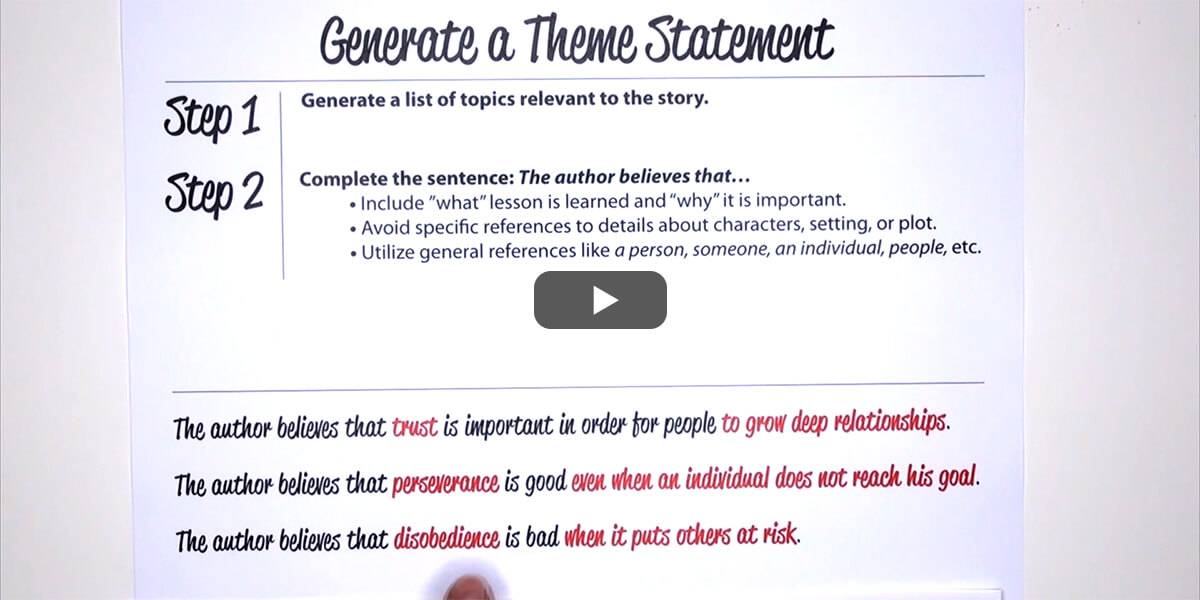

Lessons lead to themes

These three steps are part of the initial teaching of theme. However, these simple life lessons are not themes.

Themes go a step further; they explain the significance of the lesson. Why is it important to be kind to others? What’s the impact of accepting (or not accepting) yourself? What if one doesn’t realize choices have consequences?

The ultimate expectation is that students can infer themes and support them with textual evidence. However, before writing a specific thematic statement, teachers have to first feed them examples of broad life lessons.

This was very helpful. Thank you!

Thank you for your kind words!

This helps a lot!

Cora,

Thank you for your kind comment. We’re glad to know that the information presented helped you in knowing how to teach theme. If you’re interested in learning more about theme, here are a couple of articles that might be helpful.