writing

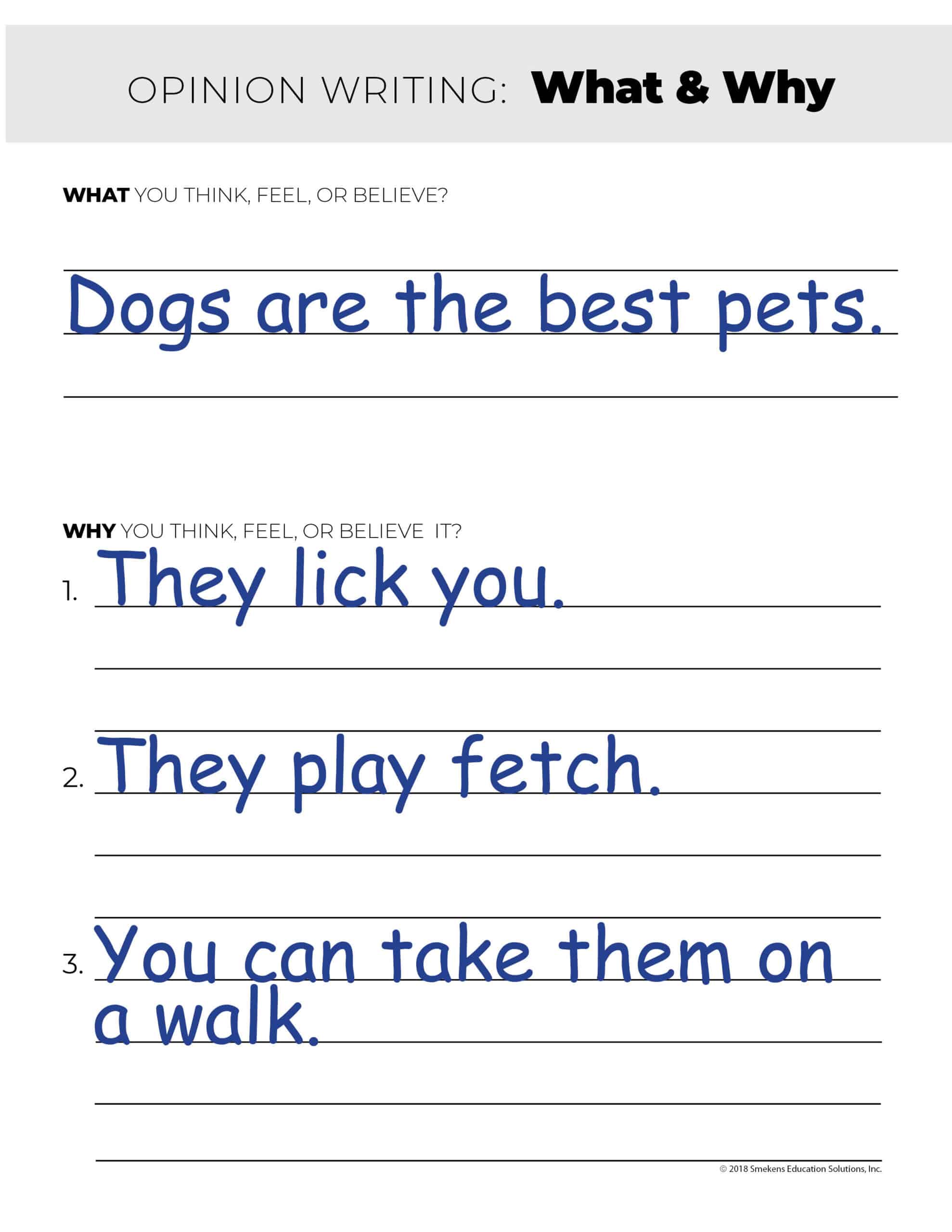

Require WHAT & WHY in primary opinion writing

Opinion writing is a natural mode of communication for young children. They have a strong sense of right and wrong, fair and unfair. This is evident as they tattle about injustices they’ve witnessed or personally experienced. It’s also how they often frame requests or proposals. Can we have a little longer for recess since it’s such a nice day? Can I go first since it’s my birthday?

Point out to students that each of these statements is intended to persuade and follows a WHAT-&-WHY organization.

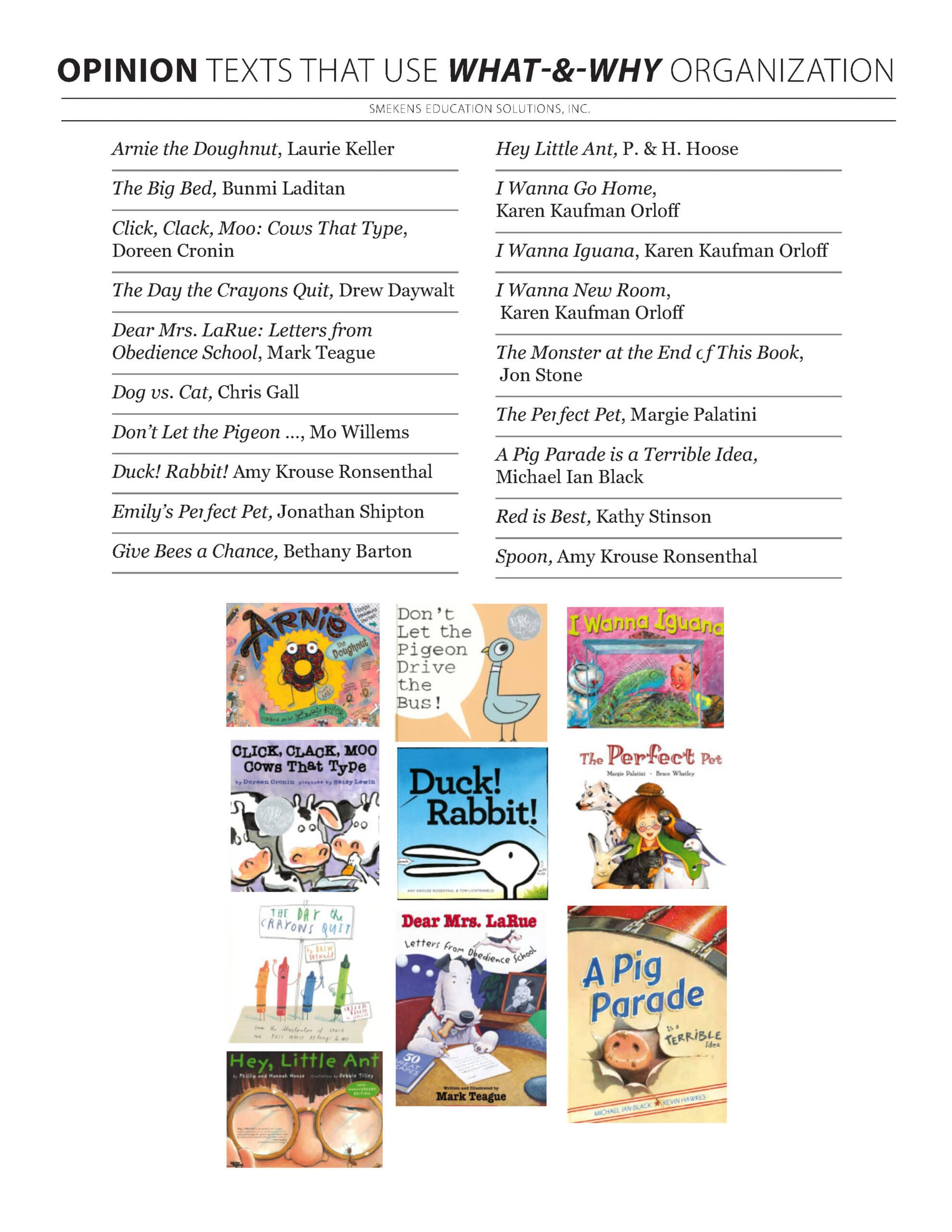

Build their understanding by first returning to familiar texts to identify the WHAT opinion and WHY details. Then transition from reading to persuasive writing, emphasizing these same two parts.

WHAT I think

The beginning of persuasive writing always includes WHAT the writer thinks or believes about a topic. If we use a train as a visual trigger to depict idea development, WHAT the writer thinks, or his opinion, serves as the train engine. (Prior to writing the beginning, teach students how to choose the strongest side.)

The beginning of persuasive writing always includes WHAT the writer thinks or believes about a topic. If we use a train as a visual trigger to depict idea development, WHAT the writer thinks, or his opinion, serves as the train engine. (Prior to writing the beginning, teach students how to choose the strongest side.)

In the primary grades, these WHAT statements often start with sentence frames (e.g., I think…., I like…., I feel…., I want…., I wish…., My favorite…., is the best.). For example:

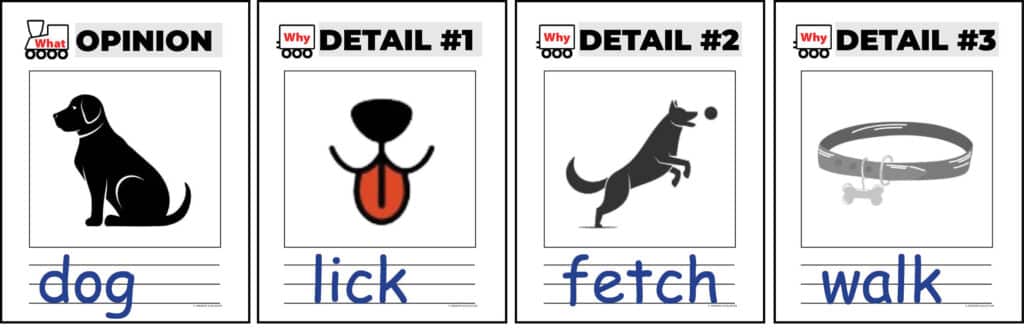

- I think dogs are the best pets.

- My favorite restaurant is McDonald’s.

- I feel that Bluey is the cutest character.

While these sentence starters for opinion writing aren’t necessary, they do tend to prompt students to not just tell information but to reveal a preference or make a choice.

All persuasion includes the writer sharing his opinion or stating a preference. And while everyone is entitled to his own opinion, persuading someone to agree with a particular position requires that the writer explain his thinking by offering support.

Opinion Writing Templates | Pictures, Labels, & Words | Sentences

WHY I think it

Explain that a writer gives the reader details for WHY he thinks WHAT he thinks. And he writes these on the middle cars that come after the train engine.

Explain that a writer gives the reader details for WHY he thinks WHAT he thinks. And he writes these on the middle cars that come after the train engine.

While coming up with WHAT you think may be easy, it’s harder to come up with WHY you think it. A powerful strategy to help students think of these WHY details is to have them picture the choice in their heads.

Model how you close your eyes and imagine yourself doing things with a dog (the best pet) or looking at a picture of Bluey (the cutest character) or sitting at McDonald’s (your favorite restaurant).

Think aloud about WHY do I want this? WHY do I think this? WHY should I get this or have this? Why do I need this? These specifics will become the WHY-I think-it details.

Initially, expect one WHY detail. Then gradually push for two and three details. Explain that more details help to persuade the reader. Model where to add these written or drawn details within the middle.

Now I want to point out a subtle but significant instructional point. Avoid calling the WHY “reasons.”

Although some primary writing standards may  mention “reasons,” think of this as a more generic word for supporting details. K-1 writers DO include small, specific WHY details.

mention “reasons,” think of this as a more generic word for supporting details. K-1 writers DO include small, specific WHY details.

Both of these versions (to the right) demonstrate exemplary persuasive writing for a K-1 student who provided three WHY details. But neither example provides three reasons.

Both of these versions (to the right) demonstrate exemplary persuasive writing for a K-1 student who provided three WHY details. But neither example provides three reasons.

When students hit the intermediate grades and beyond, reasons represent paragraphs. The reason serves as a topic sentence with the small details and specific examples described in supporting sentences.

A reason is based on several smaller WHY details grouped together. “They lick you” can be combined with “They lie by your feet” and “They follow you from room to room.” And together these support the opinion that dogs are the best pets: “One reason is because dogs show love.”

While this is far too complex for K-1 writers to do, it’s the rationale for primary teachers to define the support that K-1 writers can do as providing “details.” Remember that the instruction provided in the primary grades is preparing students to write future paragraphs. Waiting to introduce the term “reasons” until grades 2 and up helps avoid students’ future confusion.

End with a sense of closure

Although the WHAT-&-WHY text structure doesn’t specifically reference the content of the ending, young writers are expected to provide a sense of closure. Continuing the train analogy, this is the caboose.

Although the WHAT-&-WHY text structure doesn’t specifically reference the content of the ending, young writers are expected to provide a sense of closure. Continuing the train analogy, this is the caboose.

- One common option is to end by restating the opinion. (This honors what your students will do in later grade levels where the standards expect them to restate their claims within the conclusion.)

- Beyond a literal repeat of the opinion, K-1 writers could also share how they would feel if their proposals or requests were granted.

- And for students who are writing a review or recommendation, this is where they might include their star-ranking or thumbs-up / thumbs-down rating.

By teaching K-1 students the WHAT-&-WHY persuasive structure, they can begin expressing and supporting their own opinion writing with confidence and clarity.

Useful and practical!