Learning Center

writing

Compare argumentative vs. persuasive writing

october 17, 2023

Before writing a persuasive essay or argumentative paper, students need explicit instruction on the subtle but significant differences between them.

Before writing a persuasive essay or argumentative paper, students need explicit instruction on the subtle but significant differences between them.

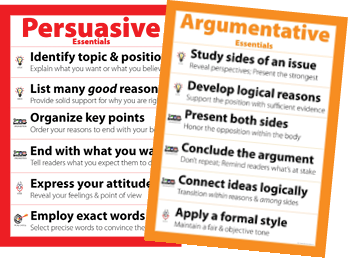

While showing persuasive or argumentative essay examples can be helpful, students also need a concrete and specific list of the ingredients found in each type.

Topics & Perspectives

All opinion writing starts with stating a position, stance, or claim. However, the nature of opinion writing is that these topics are debatable—there are differing opinions as to what is correct, fair, or best. And according to the standards—the inclusion (or exclusion) of multiple perspectives is the biggest difference between persuasive writing and argumentative writing.

Organization & Structure

All genres of argument (e.g., opinion, review, recommendation, persuasive letters, speeches, debates, argument, etc.) utilize a what-and-why structure. The beginning introduces what the writer thinks (e.g., his claim, opinion) and the body outlines why he thinks it (e.g., reasons with evidence). The difference between persuasive and argumentative comes within the body of the written piece.

PERSUASIVE: Traditional instruction encourages starting with the strongest reason. But this means that the reasons will weaken and fizzle by the end.

A more powerful approach would be to leave the reader pondering the best reason. To create this effect, present the reasons in a 2-3-1 order.

First, rank the reasons, determining which is the number one best reason. Which one will resonate with the audience best? That reason should be saved for the final paragraph of the body.

Then, identify the weakest reason of the three. It should be buried in the middle position, leaving the second-best reason to be explained first.

This organization allows students to start with a solid first reason and save their best for last. Leaving “the clincher” for the final body paragraph provides a strong segue into the conclusion.

ARGUMENT: This more sophisticated genre also has 3 (or more) reasons presented within the body. However, with an argumentative piece, there is the added challenge of incorporating the counterclaim.

Ideally, points from the opposition are woven into each of the body paragraphs. After identifying and elaborating on one reason, the writer transitions to explain the opposition’s counterpoint (e.g., However, On the other hand, etc.). Then the writer either concedes or refutes it before introducing the second reason. This They say/I say organization intermixes the strengths and limitations of both perspectives. (TIP: Show this by color coding the two positions.)

Although this is a more sophisticated structure, initially it may be easier to simply develop the counterclaim within its own body paragraph. Insert this additional information all about the opposition after the weakest reason—but before the best one. This would adjust the organization to be: 2-3-CC-1.

Audience & Point of View

A writer tailors his message to the audience—or intended reader. An awareness of the audience impacts the formality of the writing.

If the writer uses first-person pronouns (i.e., I, me, my), he implies a prior relationship between the writer and the reader. This can make the writer—and thus his opinion—more personal. Conversely, third-person pronouns maintain distance between the writer and reader—keeping the communication formal and among strangers.

PERSUASIVE: Academic writing—including persuasive—typically avoids using first-person I and second-person you. However, there are exceptions in some persuasive writing.

If the intended audience is a specific individual or a group, then direct the persuasive message to them explicitly. This might include naming the audience within the opening or greeting and/or speaking directly to the reader using an occasional you. Acknowledging this personal connection between reader and writer can actually strengthen the persuasive tone.

ARGUMENT: Argumentative writing is much more formal. There is no relationship between the writer and reader. Thus, it is always written using third-person pronouns.

Although the writer is sharing his opinion, he replaces I with advocates and supporters and substitutes you with opponents and adversaries. This word choice is essential when writing about a debatable or controversial issue that is already fueled with personal emotion.

The more formal third-person point of view helps maintain a tone of fairness and reasonableness. It keeps the focus on the subject matter—not the feelings of either the writer or the reader.

Tone & Attitude

In addition to teaching students what information to reveal in each body paragraph, provide instruction on how to say it.

PERSUASIVE: Although voice is an obvious element of persuasion, writers consider the emotional tactics that will resonate best with their audience. He may present one reason using a disgusted tone, a second reason using a sympathetic voice, and his final reason leaves the reader feeling motivated and inspired.

CAUTION #1: While making strong emotional appeals can fuel persuasive writing, a string of voice-filled and passionate pleas are NOT enough to support an opinion that lacks proof (i.e., evidence, facts, data, quotes).

CAUTION #2: It’s easy to become passionate when explaining only one side. However, avoid any polarizing comments about the opposition (e.g., You’re dumb if you think…).

ARGUMENT: It’s not that argumentative writing lacks voice. Rather, the tone is simply not as outwardly passionate as the one-sided persuasive.

With the addition of the counterclaim, the writer attempts to demonstrate he is knowledgeable and fair-minded about the issue. This is intended to speak to the skeptical reader and ultimately influence his thinking. Consequently, the writer maintains an objective tone relying on his logical reasons substantiated with evidence. The writer convinces the reader with his information—not his emotion.

At the secondary level, this ingredient of argumentative writing usually includes additional instruction on ethos, pathos, and logos.

While there are differences between persuasion and argument—there are also several similarities—including how the claim is determined and reasons are inferred.

Research & Position

Whether writing a one-sided persuasive or a multi-perspective argument, the writer always enters the process by researching the topic. He gathers information on both/all sides. After studying the issue and the evidence available for all perspectives, aligns with the strongest position—the one with the most evidence. This then converts into his claim or topic sentence.

Reasons & Evidence

When gathering the evidence to determine the strongest side of a persuasive or argumentative, the writer makes a list of facts collected from texts. Each of these text details is potential evidence the writer may cite—but none are the student’s own reasons.

In a persuasive or argument, the student must present his reasons to support his opinion. All the details he has collected from text came from other authors—other sources. None are a result of his own thinking.

Consequently, a student must combine several related text details and generate a common category that they all fit. That category or idea is a reason. Then, the grouping of text details serves as the supporting evidence.

According to the college and career-ready standards, the answer to What are persuasive essays—versus the more sophisticated argumentative writing—comes down to several factors. Therefore, it makes sense that presenting a one-sided persuasive is the standard at the elementary level. This is the foundation of a future argument in middle and high school. If a student can’t woo the reader when presenting one perspective, he will struggle when he must juggle and present two.

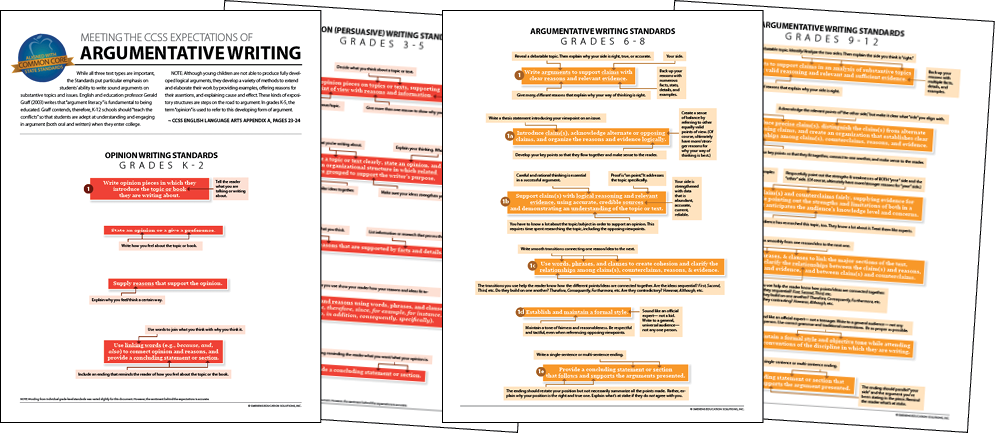

Purchase a set of Genre Essentials posters to use during your daily writing mini-lesson instruction.

Purchase a set of Genre Essentials posters to use during your daily writing mini-lesson instruction.

Purchase a set of Genre Essentials posters to use during your daily writing mini-lesson instruction.

Thank you for providing detailed and distinct explanation between the different writing styles.